Le Roi et l’Osieau is a French film which also features an organ grinder and a Hitler allegory – this time not in the same person. The film was in production from 1948 and had a partial release in 1952, but was not completed until it’s release in 1980(!). There also exists a ‘low-budget English-language release of the 1952 version, titled The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird, [which] is in the public domain and available free’ on archive.org. (Wikipedia)

I was only able to find the 1980 version in French, without subtitles. I was able to follow it because I had watched My Wonderbird first. The films contain large, sprawling stories, with a lot of plot, and a clockwork punk aesthetic. They have all the surrealism of Soviet children’s cinema, but (especially Wonderbird) also uses Disney-esque archetypes. With a king and a shepherdess, it has elements of a bucolic fairytale, but with a chimney sweep and organ grinder, this is intermixed with urban elements.

The king lives in a hyper modern police state, called Takicardie, surrounded by machinery – literal mechanisms of power – and guards. Although he is a fairytale character, his statement that “work is freedom” could not be a clearer allusion to Nazis and Auschwitz.

The heroes of the film are a chimney sweep and shepherdess who wish to marry, despite the king’s insistence the shepherdess should marry him. The narrator, a mocking bird, also plays a major role in the action.

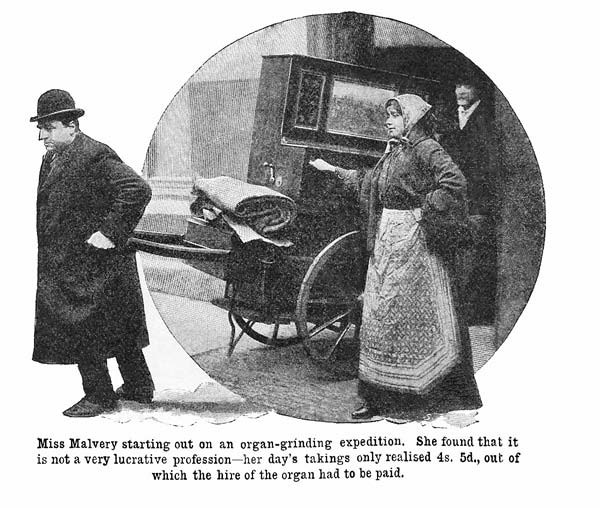

The organ grinder is a supporting character, introduced late in the narrative. He is subaltern, literally living in the underground. The proletariat is so alienated from their labour and the results thereof, that they know of the sun and birds only as fairytales.

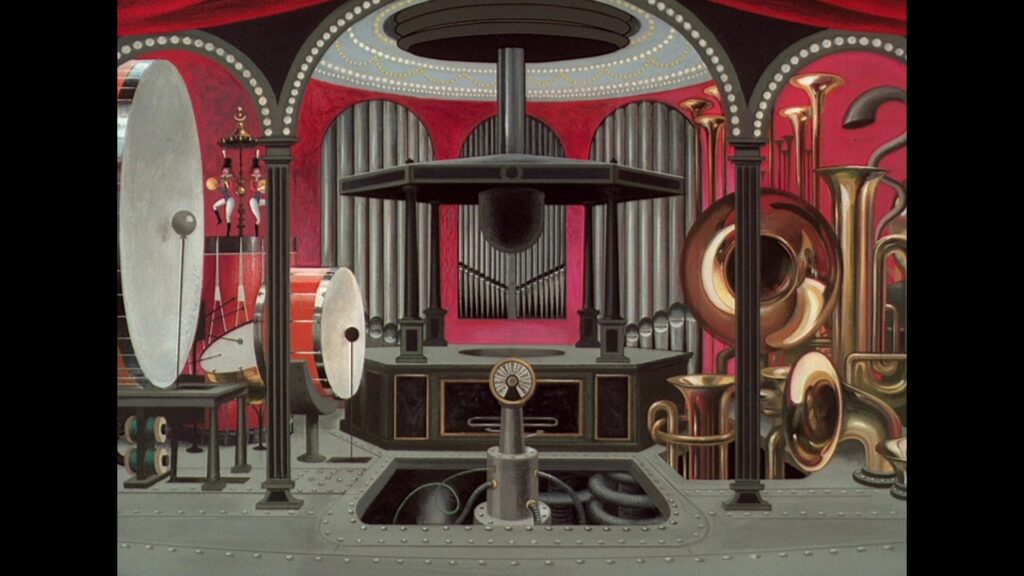

As far as the sound design goes, the two films have some difference. Wonderbird uses music that could conceivably come from a busking organ for the organ scenes, whereas the later version treats the instrument more as a Victrola. For the scenes with the giant robot, in Wonderbird, the sound effects of the giant robot emphasise the sound of the machinery itself. Giant, grinding sounds and gears, as well as destruction, like breaking cement. In the 1980 version, the robot itself is quieter and the sounds of things breaking is foreground. Those are the sounds of wooden boards being dropped.

The earlier version (or perhaps anglophones?) envision the proletariat in modern blocks. Whereas the French in 1980 had them in historic wood-framed housing.

The later version also gives more clues as to the primary industry in the society, although this is present in both versions. The workers toil to produce representations of the king. All commerce is created directly in his image. Or is in service of his entertainment and power.

There is therefore a strong resonance with generative AI. The ruling class creates its own image, without real meaning, over and over again.

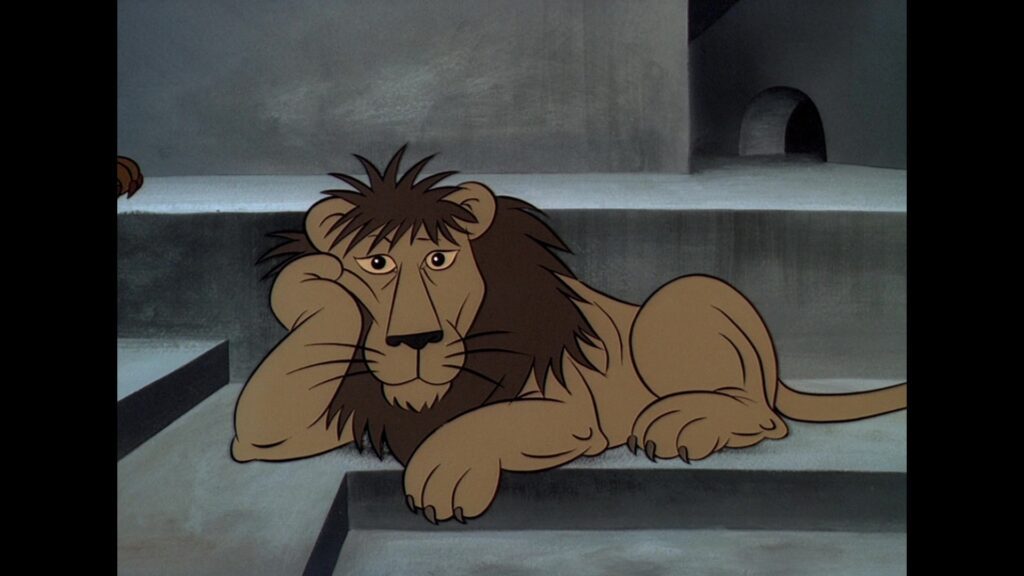

In both versions, the organ grinder plays absolutely necessary political roles both in keeping the proletariat hopeful and ready to participate in the revolution, and also in winning over the king’s lions to rise against him. He is especially vital in playing for the lions, who would have eaten the main protagonists if not for his intervention.

The 1980s version, in addition to removing the sonic references to a busking organ also portrays mechanical organs generally as a neutral technology. The king’s giant robot has quite a lot of space set aside for a fairground organ within it. This organ does play music that could realistically emit from it. It has a large number of tuba-like pipes. These low brass sounds are used to ominous effect and indicate menace.

The epilogues of the two films also differ. Wonderbird ends with the survivors of the regime collapse living in an idyllic camp near the ruins of the urban centre. The 1980 version, has a more satisfying emotional tenor in which the robot has become both disables and autonomous and acts to smash one of the king’s remaining cages. Although this is the right emotional tone, the political messaging is more muddled. The master’s tools do take down the master’s house.

Comparing Brundibar and Le Roi

In the wedding scene of Le Roi, all of the guests are male guards – oddly modelled on Victorian Englishmen. The society is clearly very class stratified, but this is mostly expressed in terms of military command. In that scene, there is also a propaganda agent, taking a pseudo-journalistic role, while also instructing the crowd when to cheer. He seems to be a parody of Soviet reporting. The king’s art museum also has a docent/security guard who ranks below the king’s guard and is abused by them. The guards themselves who are of equal rank appear to behave equally. The proletariat are also apparently equal among themselves.

It’s perhaps not overly useful to compare this fairytale society with actual Nazis, but to do so anyway: The SS’s structure promoted camaraderie and downplayed command structures, so being within it felt relatively flat. However, there was a very clear hierarchy between members and non-members.

By contrast, Brundibar both is and is not a fairytale. It has talking animals, but the organ grinder is grounded in material conditions. As an allegory, his actions both lie within fairytale logic and how children might perceive adult actions regarding rules they do not understand. Unlike Le Roi, only the subaltern is present. The opera has only civilian characters and depicts an extremely unequal society, in which I argued previously, the organ grinder is a middle class between less privileged buskers and patrons. In his paper, The Social Basis of Fascism Sinclair suggests that a more accurate term would be ‘middle strata’, which is ‘preferable because it conveys the idea that included share an intermediate position in the status structure of a society, although they may belong to different classes.’ (p 101) While it would normally defy credibility to imagine any busker as in an intermediate class, we can perhaps justify it here from the fairytale view of children who are definitively below Brundibar, the organ grinder, in the social and class hierarchy.

But what did fascism mean for the middle strata? In 1936, Barnes wrote about the relationship between fascism and the middle classes. He writes, fascist ‘popular electoral campaigning has been directed chiefly to the middle class. It has been most successful in those countries where a disaffected petit bourgeois class is allied in politics with a land-hungry peasantry. Especially in its initial struggle for power and to some extent as a continuing policy, Fascism has looked to these groups for its popular support.’ (p 25) But these groups are not naturally united. Their ‘attempt “to formulate a coherent, workable system is handicapped at the outset by the fact that as a class it possesses the homogeneity neither of the trust bourgeoisie nor of the proletariat. It is a mixture of heterogeneous elements, some in undisguised conflict.” ‘ (p 27) Thus suggesting that fascism’s middle strata are a coalition of groups seeking greater power. The inherent instability turned out to not be a material problem for fascist countries, who in reality organised for the benefit of corporate monopolies. ‘Power once achieved, the forgotten man [of the middle strata] was once again forgotten.’ (p 28) The fascists thus used a disparate and divided group of people who felt some privileges to gain power while actually ignoring their concerns.

In Brundibar, the eponymous organ grinder steals the children’s takings, which he believes are rightfully his. In terms of Eco’s ideas of Ur Fascism, he feels frustration, so he takes action. This speaks to the every day, individual experience of fascism, which is often expressed as conflict between individuals who are empowered or disempowered under the unjust systems. It is not Donald Trump out shooting bystanders, but swarms of ICE agents who are terrorising communities.

If Brundibar is a warning against social hierarchy, and a reminder that in a fascist state, we are surrounded by little dictators, what can Le Roi teach us? Cooksey writes, ‘Begun in the wake of European fascism and the occupation of France, Le roi references totalitarian spatial design and the iconic images of the dictator. By underlining their construction, the film satirizes and subverts the authority claimed by the spectacle of fascist grandeur.’ (p 210) As to the mechanics of this, Cooksey writes, ‘Takicardie’s chief industry is devoted to the mass-reproduction of the King’s image, reduplicated throughout the city in paintings, sculpture, and even topiary. In a symbolically relevant turn, one of the images of the King escapes from a recent portrait, replacing the actual King. In this political allegory, the image of the face becomes the literal controlling master sign, defining everything in the kingdom.’ (p 214) Politically, our heroes are inherently opposed to this, ‘The identity of shepherdess links her with the pastoral, while that of the chimney sweep with the urban. We might recall William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Together their love points to an alliance of town and country, broom and crook instead of hammer and sickle.’ (ibid)

As the film progresses and characters are thrown to beasts, ‘The [blind organ grinder], who knows only perpetual darkness, is so inspired [by Mr Bird] that he begins a sad but hopeful song. . .. Moved by this song and Mr. Bird’s oratory, the beasts spare the prisoners and then break out of the den, forcing their way out of the subterranean city and upward into the palace, where they disrupt the King’s forced wedding to the shepherdess, primal forces emerging from the lower depths (the id), to disrupt and shatter the superego.’ (p 216) Thus emphasising the role of the arts as a force for resistance. Indeed, Duggan writes, ‘The film valorizes artistic and political freedom.’ (p 75)

However, as the king’s second, larger organ also suggests, Cookes notes the ‘underlying theme of fascist spectacle and the connection between the regime of signs and the despotic.’ (p 216) Art can be used for good or for evil. In the world of Takicardie, this is most often expressed via architecture, ‘Here the city and its public buildings are conceived as works of art that establish social strata and ceremonial spaces. With its monumental buildings, its formal manipulation of heights, creating hierarchies between the public and the domestic.’ (p 217) In Brundibar this is primarily expressed via social relationships, but the fairytale king of Takicardie has greater scope to create material conditions. The style of the king’s city ‘was the style favored by the totalitarian regimes of the 1930’s.’ (ibid)

As to the music, the timbres of the king’s organ reflect the sheer size of it and do reflect an assertion of power. However, the styles and content does not otherwise seem to link to the allegory. Indeed, the affordances of actual organs are not considered by 1980.

The film, especially the latter version, suggests no particular action but merely affirms that fascism is bad and freedom is good. The absence of a call to action in children’s media is certainly a reflection of the safety in which it was made.

Works Cited

Barnes, J. (1936). The Social Basis of Fascism. Pacific Affairs9:24.

Cooksey, T.L. (2019). Pataphysical Assemblages: Fascist Spectacle in Paul Grimault’s Le roi et l’oiseau. The Comparatist43:209–227.

The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbir (1952). Clarge Distributors. 63 minutes.

Duggan, A.E. (2015). The fairy-tale film in France: Postwar reimaginings. In: Fairy-Tale Films Beyond Disney. Routledge, pp. 64–79.

Eco, U. (1995). Ur-fascism. The New York review of books22:12–15.

Hans Krása (1938). Brundibár. [Opera].

Le roi et l’oiseau (1980). 83 minutes.

Sinclair, P.R. (1976). Fascism and Crisis in Capitalist Society. New German Critique:87.

Toltz, J. (2004). Music: An Active Tool of Deception?: The Case of’Brundibar’in Terezin. Context: Journal of Music Research:43–50.

Wikipedia (2026). The King and the Mockingbird. Wikipedia [Online]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_King_and_the_Mockingbird&oldid=1333784331 [Accessed: 21 January 2026].